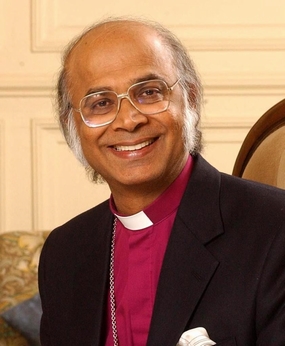

Bishop Michael Nazir-Ali grew up in Karachi, Pakistan and was the Bishop of Rochester for 15 years. He has since devoted his time to advocating for the persecuted church, most recently as Director of the Oxford Centre for Training, Research, Advocacy & Dialogue. I had the privilege of meeting with him in July to get his thoughts about the future of the Middle East and North Africa in light of the recent protests.

Bishop Michael Nazir-Ali grew up in Karachi, Pakistan and was the Bishop of Rochester for 15 years. He has since devoted his time to advocating for the persecuted church, most recently as Director of the Oxford Centre for Training, Research, Advocacy & Dialogue. I had the privilege of meeting with him in July to get his thoughts about the future of the Middle East and North Africa in light of the recent protests.

Is Democracy Enough?

By-Wazala

Opinion

00:08

Sunday ,07 August 2011

It was impossible not to be moved by the pictures of thousands of people gathered in Tahrir Square calling for freedom and democracy in the early spring. The sight of Christians and Muslims standing together in solidarity brought such hope for the future. Was this the beginning of the end for authoritarianism, signalling a new dawn of democracy? Months on, we still see protests across the region but I can’t help but feel the mood has changed. Egypt has overthrown its dictator, who cast a shadow over the country for 40 years, but still does not have freedom and democracy. There is an increasing lack of security due to the breakdown in state apparatus and the elections have had to be postponed from September until November because the country simply isn’t ready. Conflict between the rebels and Gadaffi forces continues in Libya, and in Syria the government is taking a hard line against protestors and is refusing to make any concessions. Can the democratic dream become a reality?

In our recent interview with Bishop Michael Nazir-Ali, he stated that ‘democracy is not enough’ for the Middle East, raising an important question about the nature of democracy and its role in a fair and just society. What do we mean by ‘democracy’? Multi-party elections and the right to vote are not enough; surely it’s about something broader. But is it compatible with every society and does it have inherent values?

The values of liberty and equality have been integral to our form of ‘liberal democracy’ in the West since its conception. As a result, we expect that everyone, regardless of ethnicity, religion, race or sexuality, will be treated equally and fairly and governed by the same rules. It would be a big deal if somebody’s liberty was not respected in our society. And yet, can our form of liberal democracy fit every culture?

The Arab Spring has witnessed thousands of people calling for democracy but will it result in a fair and just society? Bishop Nazir-Ali argued that democracy could simply turn into the tyranny of the majority unless it is accompanied by a strong commitment to liberty which safeguards freedom of expression and belief and a commitment to equality of all before the law. He suggested that what people are mainly talking about through the Arab Spring would be more accurately described as accountability rather than democracy. He criticised the narrow focus on democratic elections without developing a discourse about what kind of values will define it. Accountability is a really positive step and is crucial, but he warned that it needs to be accompanied by the other democratic values of liberty and equality if it is going to live up to the dream.

Regarding the ‘tyranny of the majority’, Nazir Ali suggested that if an ‘Islamist party were to win democratic elections by a majority and went on to implement Sharia Law it could compromise both liberty and equality and still remain in theory democratic’. For example, at a basic level there could be blasphemy and apostasy laws which would restrict the freedom of expression and belief for Christians and other minority faiths. He was keen to point out that his ‘concern is not only for Christians but for women too’ who could have many freedoms they enjoy in many Arab states taken away.

Consider Egypt, where there is a real possibility that this could happen because the moderate parties are currently not organised enough. Were that to happen, he believes that there would be some legal concessions for Christians because the Christian minority is so significant, representing over 10% of the Egyptian population. However, he warned that this would create a two tier legal system, which would in effect go back to the situation under the Ottoman Empire, when there were different laws for different groups. This would clearly undermine any notion of equality of all before the law. Stating it would immediately result in less integration which would fuel separation and division between communities, he argued that it would be detrimental to the future of Egyptian society.

The acid test of democracy according to the Bishop, is whether people are willing to give up power as well as to gain it. The question we should be asking is, ‘are the people who are getting involved in democracy [Arab Spring movement] actually committed to democracy which includes losing power?’ After all, there are numerous dictators who have won power democratically but refused to let it go. Interestingly he makes a connection between Christianity and democracy: 'the implication in democracy about losing power has come from a Christian background because the Christian worldview has been shaped by the cross which means that it is in the losing of power where Christ is glorified'. This is extremely counter-intuitive to human nature and yet it is what is needed.

Despite his concerns, Bishop Michael believes the Arab Spring will cause a lasting change in the sense that people are now conscious that they can remove even strong men, and that knowledge will not go away and may be used again in the future. This kind of empowerment can only be a positive step but we must pray that there is an awakening of the importance of the values of liberty and equality if the Arab Spring is going to deliver on its promises and become an opportunity for the gospel. Democracy was never going to happen overnight, it’s a journey.