The Seven Pillars of Egyptian Identity, a book by the late Coptic intellectual Milad Hanna, will be a main reference at the World Youth Forum held in Sharm El-Sheikh from 3 to 6 November.

The organisers want to study the main characteristics of Egyptian identity, because of its effective role in many civilisations. The book by Hanna stresses the importance of the unity of society and its “seven pillars”.

During the Greater Bairam prayers held on 24 September 2015 at the Hussein Tantawi Mosque in Cairo attended by President Abdel-Fattah Al-Sisi, Sheikh Osama Al-Azhari selected “Egypt s status in Islam” as the topic of his sermon.

Throughout the ages, God had blessed Egypt with security, Al-Azhari said, referring to the Quran verse 99 from the Surat Youssef, “Enter Egypt, God willing, safe and secure.”

Al-Azhari said that foreign conspiracies had sometimes targeted Egypt s capabilities, but that these had been foiled by the Egyptian army that had managed to stop all aggressors.

This was because Egyptians themselves had great willpower, he said, never losing hope or getting disappointed. In addition, the Egyptians had the ability to rebuild themselves following crises and become much stronger.

Al-Azhari said that the Egyptian man was a leader who knew how to evaluate his capabilities and who loved his homeland and realised its position among other countries.

Hanna s name was also mentioned, as though he passed away in 2012 he left us an important book in his The Seven Pillars of Egyptian Identity that emphasises the unity between Muslims and Copts.

Hanna was an engineer by profession and a member of various international organisations. He was interested in Sudanese affairs and Nile and water-security issues.

He thought there should be a separation between politics and religion, and as a Coptic intellectual he wanted to see the Egyptian Coptic Orthodox Church play its role as a religious institution and not have any political role.

Hanna won several European prizes, as well as the Egyptian State Appreciation Prize for Social Sciences in 1999. Among his books are Copts but Egyptians, Studies and Working Papers on Housing Issues in Egypt — he was also a housing expert — September Memoirs (about his detention during the Sadat period), The Clash of Cultures, The Human Alternative, and Politicians and Monks Behind Bars.

When Hanna was asked about the title of his book on Egyptian identity, why the number seven, for example, his answer was simply “why not?” Some tried to link the title with a verse in the Biblical Book of Proverbs: “Wisdom has built her house; She has hewn her seven pillars.”

The main idea of the book is that place and time leave a deep impact upon every one of us, regardless of culture or education or whether one is a university professor or a simple farmer.

Every Egyptian from the Pharaonic era until today, and passing through the Graeco-Roman period, the Coptic period and then Islam, is deeply influenced by the place he lives in, Hanna feels.

He is an Arab because Egypt lies in the heart of the Arab nation, a Mediterranean man because his country borders the great basin around which many world cultures were formed, and an African because of his belonging to Africa, in which Egypt lies in the north.

So long as all of us have these seven pillars to our personalities, it is natural to find one group of people preferring the pharaonic belonging, while another group rejects it, considering the Arab and Islamic pillars to be alternatives, Hanna says.

Although such pillars or belongings exist inside all of us, they are not equal in length or strength. The degree of each will differ from one person to another, in accordance with the human or personal structure of each. Moreover, with the passage of time interest in a certain pillar may change.

During youth, the primary belonging may be to the homeland, religion, or Arab nationalism. However, as he gets older a man s experience will mean other forms of belonging may grow inside him, and he will start to view things in less black-and-white terms.

Not Politics:

The Seven Pillars of Egyptian Identity is not a book about politics, with Hanna asking “in the end, what is politics? Isn t it a just a stance, an ideology, and an attempt that makes man happier and helps him discover his ambitions for the sake of a better future?”

It is not exactly a book about sociology either. Man is by nature a sociable creature, who interacts with others.

It is not a book on psychology. Psychology looks into the psyche of individuals and groups and helps man discover himself and thus reach happiness.

It is not a book on philosophy, though its author would perhaps have liked to be a “lover of wisdom” and a student of philosophy, a subject that goes beyond politics and everyday reality.

It is not a book on human rights, which in the West means protecting individual freedoms. In the Arab world, the focus should be on the rights of groups and those with different belongings.

Hanna s book serves democracy, arguing that people should aim to understand themselves, their colleagues and their neighbours before conducting dialogue with them.

This will help them accept their opinions even if they differ from their own. In fact, this is the core of democracy, meaning he acceptance of difference.

He concludes the book by emphasising national unity in Egypt. The main idea is that Egypt is rich with an accumulation of experience gained from the effects of time and place.

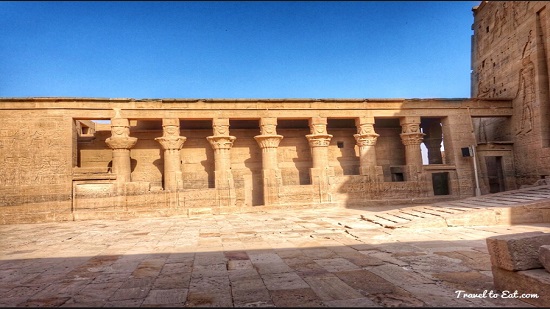

Of the Pharaonic pillar of Egyptian identity, Hanna says that all Egyptians are proud of their belonging to such a great civilisation. They are proud of the ancestors who built the first state and the first central government in history.

The Early Dynastic period (3100- 2778 BC) starts with king Menes, the unifier of Egypt and founder of the First Dynasty, he notes. Then comes the Second Dynasty and the era that witnessed the construction of the Pyramids (2778-2263 BC).

Since this date, the Egyptian character, cherished by all Egyptians regardless of their religious belonging, has been crystalised. It is one of the secrets behind Egypt s unity throughout the ages.

The writer moves on to 332 BC, the year when Alexander the Great advanced on Egypt and saved its people from Persian rule. The Greek pillar of Egyptian identity started with Ptolemaic rule and lasted for 300 years until queen Cleopatra came to the throne.

It ended in 31 BC, when Octavius invaded Egypt, making it a province of the Roman Empire for many centuries. The Roman pillar then mixed with the Coptic Christian one, leaving a deep impact on Egypt s history.

Hanna then discusses the Islamic pillar that followed the Coptic one in Egypt s history. Although some historians say the Coptic era ended in 641 CE, the year the Arabs gained control over Egypt, Hanna views this as inaccurate since many Egyptians did not abandon Christianity for several centuries.

The Coptic language continued as the common language of Egypt throughout the seventh and eighth centuries CE. During the ninth and 10th centuries, it was still part of daily life, together with the Arabic language.

A wave of conversions to Islam began in 969, the year heralding Fatimid rule in Egypt. By the 12th century, the Coptic language was only preserved in Christian monasteries.

With the advent of the Islamic era, Egypt started to play a key role in Islamic jurisprudence and civilisation, exactly as it did in Coptic thought. At the beginning of Fatimid rule, the first and largest Islamic institution in history, the Al-Azhar Mosque, was founded in Egypt.

Today, the Islamic religion in Egypt is distinguished by the unique cultural characteristics felt in people s daily lives.

The author s overall aim in the book is to review the geographical and historical belongings of Egyptians and to analyse the country s cultural structure in the modern age.

In his chapter entitled “Egypt Will Not Turn into Another Lebanon”, Hanna argues that sectarian storms cannot reach Egypt, of the type that led to a ferocious civil war from 1975 until 1992 in Lebanon.

Al-Azhari, in his sermon, returned to Hanna s themes and reminded me of Hanna s words that the Egyptian personality blends together ancient Egyptian, Coptic, and Muslim aspects.

As we rebuild Egypt after the 25 January Revolution, the Ministry of Education should take the initiative of setting this book for study in the country s secondary schools.